By Posted by

Published: , Updated:How to revitalize MLB’s All-Star Game

Changes to ponder for baseball's three-day midseason extravaganza

When I was growing up in the 1970s, one of the highlights for me every summer occurred on a July evening when the National League squared off against the American League in baseball’s All-Star Game.

It was appointment television, the night when the best from both leagues played a contest to prove which league was better. And from 1963 to 1982, the NL — my guys, as I was a Mets fan — won every time except one (in 1971, when Oakland’s Reggie Jackson hit the light tower in Detroit to help lead the AL to victory). Then, from 1997 to 2009, the American side was triumphant (aside from that stupid tie game in Milwaukee in 2002).

That deadlock triggered an idiotic decision by then commissioner Bud Selig, which we’ll get to later. After a brief momentum turn by the Nationals, the AL teams have regained dominance; from 2013 to this past week’s 5-3 game, the AL has won each time aside from last year’s battle.

A lot has been said, especially from people in my age demographic, about how the ASG has lost its pizzazz. There are some reasons for this that cannot be reversed.

FREE AGENCY, INTERLEAGUE PLAY CHANGE THINGS

One of the things that made the game so special was the honest-to-goodness uniqueness of seeing American and National League players facing each other, something we only got to witness in the World Series (or in spring training). But even the World Series was just one team versus another, NOT an entire cavalcade of players. It all changed with the emergence of free agency in the mid 1970s, which allowed players to sign rich contracts with new teams in either league. In the first full year alone (1976), stars such as Rollie Fingers, Gene Tenace, Don Gullett, Willie McCovey and Billy Williams jumped leagues. The separation of the AL and NL — which helped create the All-Star Game rivalry — truly dissolved in 1997 with the inception of interleague play. Now, when the Fall Classic came around in October, the chance of seeing a unique matchup took a major hit. And it’s only gotten worse with the increase of interleague games. (Whether it’s a good thing or not is another argument for another time.)

However, there are ways to make the ASG watchable again, to give it a sense of worth.

Now, I don’t mean to place some sort of importance on what is, even at its peak, an exhibition. That’s what Selig did from 2013-16, when the World Series representative of the winning side of the All-Star Game received home-field advantage for the best-of-seven set in October. It was inane thinking for many reasons. For instance, why would a Yankee want to excel in the ASG only to see the Red Sox benefit from that with a World Series Game 7 at Fenway Park?

MORE EXPOSURE FOR THE FUTURES GAME

Fortunately, that gimmick died. Other ways MLB has looked to entice viewers to the three-day spectacle have had middling success. Two days before the actual ASG, there’s the MLB Futures Game with some of the sport’s top minor-league prospects. Sometimes, they’ll divide the sides between players on AL and NL affiliates (when I went to the one in 2013 at Citi Field, it was the U.S. vs. the World). Regardless of how the sides are chosen, it’s a cool idea and a great way for fans to see the new crop of stars on the horizon. Unfortunately, the game is played in the afternoon, going up against the final MLB contests before the break! Huh? Why not schedule it for prime time, and make sure it’s on a network people can get (don’t be super greedy and give it to some streaming channel). I would say to schedule it before the actual ASG on Tuesday, maybe a 4:30 start, but the logistics of getting those fans out and the ASG fans into the stadium would be a nightmare. (The only way to get around it would be to have the Futures Game take place in a different venue, but that ruins the concept of having a “host city” for all the festivities.)

Now, on to the Home Run Derby, which has started to suffer from the same problem the NBA’s Slam Dunk Contest has: the best candidates aren’t there. It’s not as bad as basketball’s predicament — where the last dozen years have seen the likes of Jeremy Evans, Terrence Ross, Glenn Robinson III, Hamidou Diallo, Derrick Jones Jr., Anfernee Simons, Obi Toppin and Mac McClung (twice!) take home the trophy. Baseball has featured bigger names in its winner’s circle, although 2024 Home Run champ Teoscar Hernandez is, like, the fourth best Dodger you could’ve gotten to compete. For all the crap the Mets’ Pete Alonso gets for wanting to do this, at least he’s showing some enthusiasm for an event he knows little kids (the eventual fan base of the sport) actually care about. The Yankees’ Aaron Judge has begged out ever since winning the Derby in 2017.

So, I propose some changes (commissioner Rob Manfred may have to holds the MLB Players Association’s collective feet to the fire, but so be it). First, the top home run hitter from the host franchise MUST compete unless LEGITIMATELY injured, simply to juice up the crowd. Second, the top four players from each league’s HR leaders list (at a deadline, maybe a week before) will be asked to participate with only a legit injury allowing them to refuse. If there are absences, the selections will go down to as low as the 10th batter on the list, but it will not go past that. Third, there will be no head-to-head format until the final round. Fourth, the total of nine batters will compete via “old school” rules, seeing how many dingers you can smack over the course of 10 outs (with a 20-second pitch clock for the BP hurler, but no time clock for the round).

DITCH THE HORRIFIC THREADS!

As for the All Star Game itself, the biggest change would be a simple one, something almost everyone (aside from Manfred) has voiced support of: go back to having players wear their own team’s jerseys! MLB put an end to the practice after the 2020 contest. Ever since then, the league has forced players to don a variety of horrific pastel-colored uniforms that most weekend softball players wouldn’t want to be caught dead in. Baseball, unlike the other three major sports (where it’s critical for players to wear the same tops), boils down to a pitcher-versus-batter duel. They could have on the same threads and there would be no confusion. But because of Manfred’s greed on behalf of the owners, he has a working agreement with Nike (makers of this season’s see-through, small-letter uniforms!) to live up to. Still, if enough people speak up and turn the channel, maybe he’ll ask Nike to just make a commemorative patch for ASG players to wear. If Manfred is adamant about the ugly clothes being worn, just limit it to those participating in the Home Run Derby the day before.

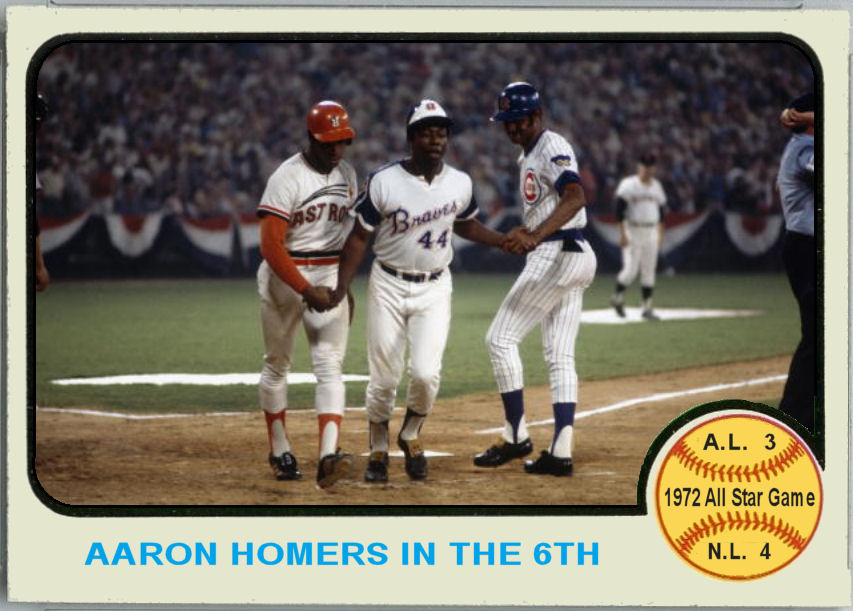

Other more meaningful fixes? Through the 1980s, the starting pitchers (unless they were rocked by opposing batters) pitched three innings. It was an honor to be selected as the starting pitcher (usually by a combination of the ASG manager, the pitcher’s own manager and the league president). I know everyone these days is touchy about arm injuries and pitch counts, so for the past 20 years, starters are almost exclusively going one inning. I’m not asking starters to pitch three again, but having them go two would be more worthy of the honor. To prove that I’m not a total curmudgeon, I actually do like the interactive elements that many of the TV networks do, like in-game interviews and players wired for sound. Those things should be increased to give fans a window into the sport. And let’s have a 30-minute pregame show exclusively devoted to putting the spotlight on this new wave of players. Heck, I didn’t know a bunch during the July 16 tilt (Garrett Crochet? Cole Ragans? Heliot Ramos?) … even game MVP Jarren Duran is basically a mystery. It’s not like the old days, when Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, Carl Yastrzemski and Brooks Robinson would be there every year.

For all of its shortcomings, the MLB All-Star Game is still the best among these types of contests. Football, basketball and hockey are no-touch offensive affairs; at least baseball’s version somewhat resembles a real game.